Being intentional about receiving consent before sharing data with AI builds user trust, provides liability protection, and supports ethical user experiences. AI-powered transcription is not a new invention of generative AI. However, now that models can be trained on our voices, and content can be generated out of our conversations, people are justifiably more concerned about the privacy of these tools.

Consent is necessary in three domains:

The first two methods of granting support for data sharing are largely covered by the the data ownership pattern. Getting consent from others to use AI to record and possibly train on their data requires its own, more intentional approach.

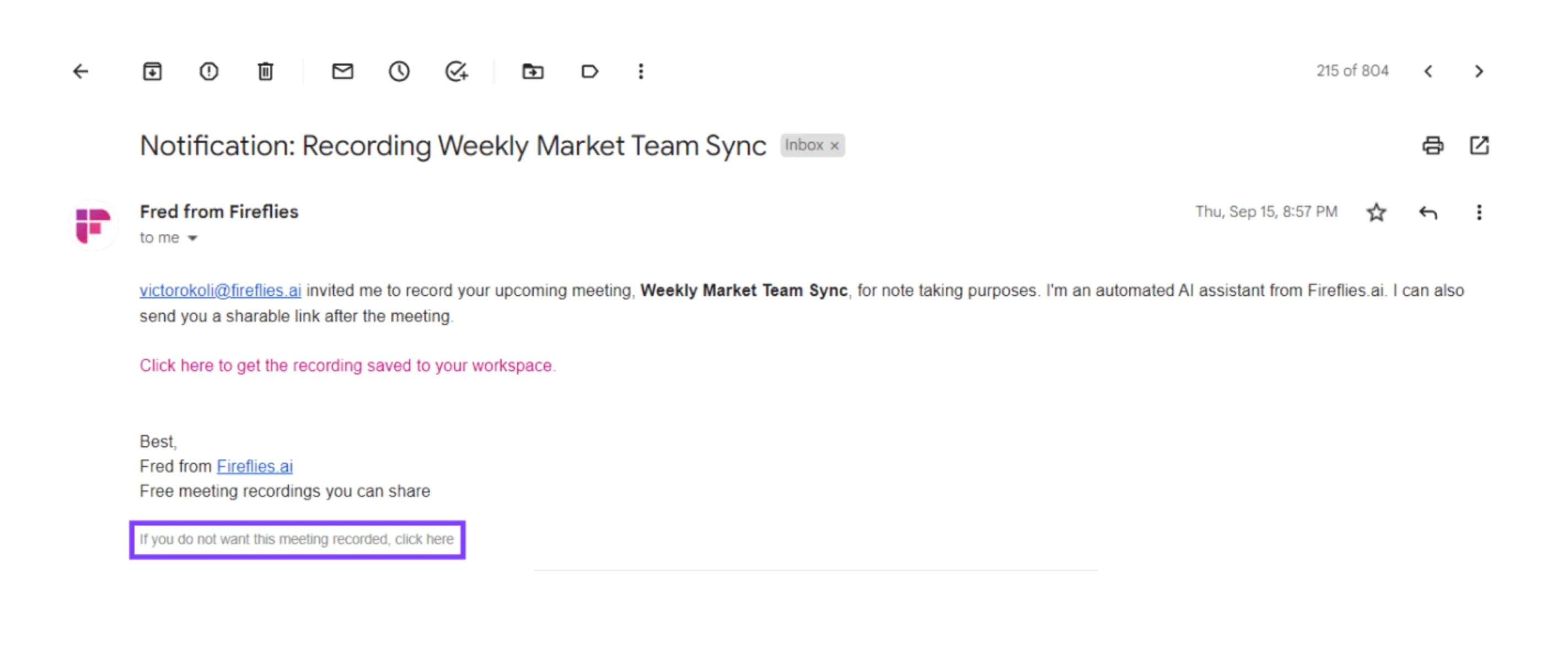

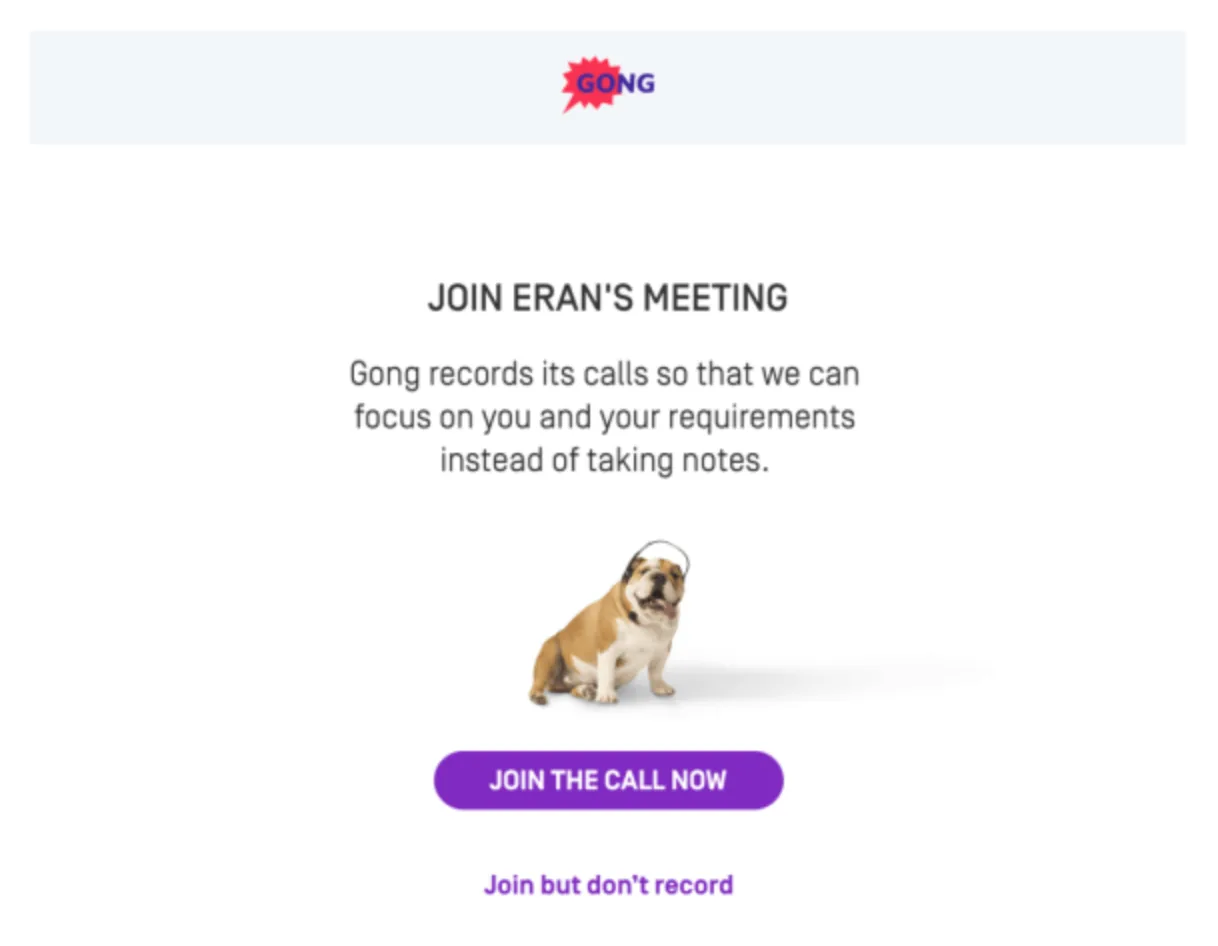

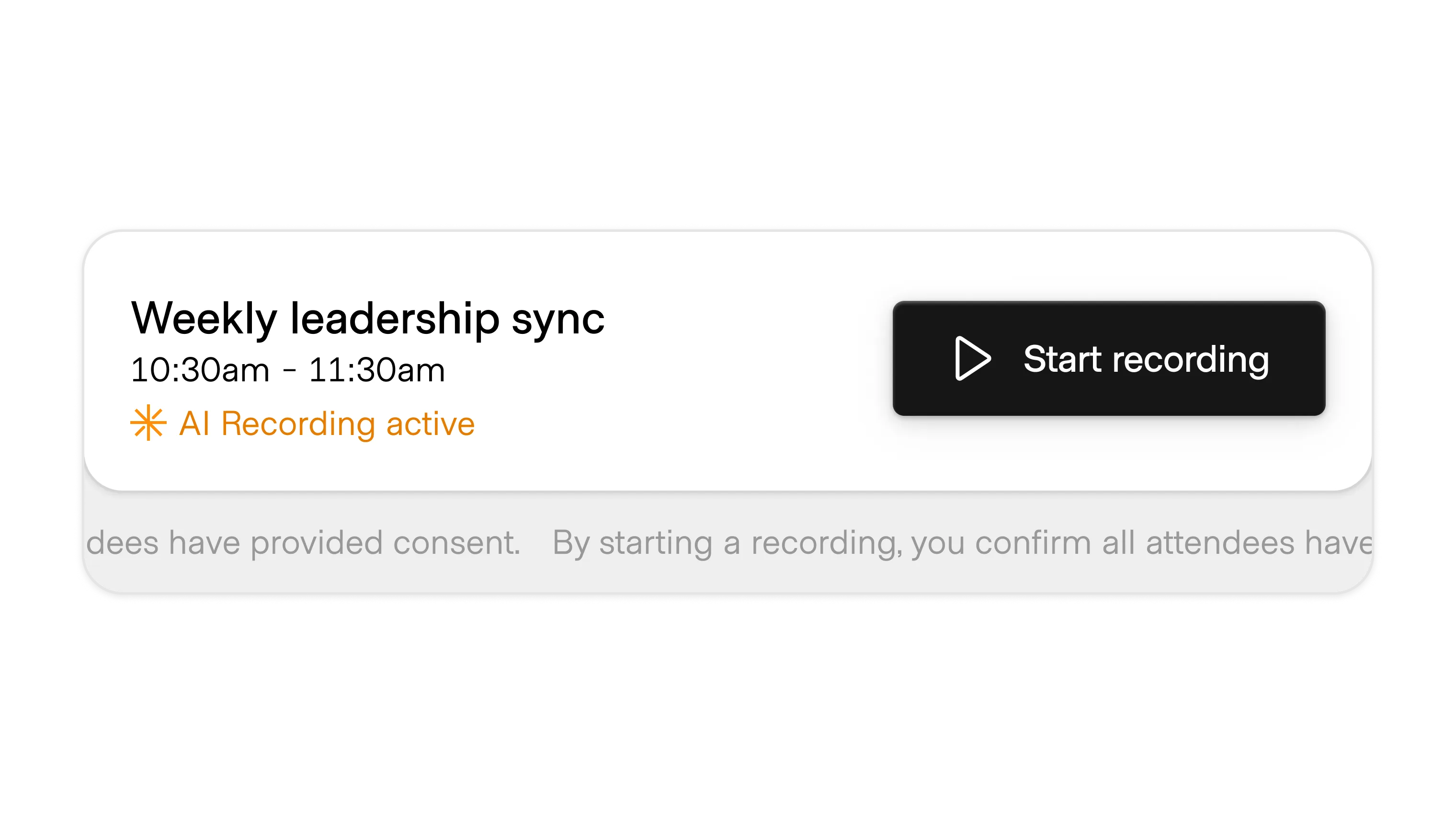

Very few products on the market proactively request consent and block recording or transcription if it is not given. Instead, this pattern takes multiple, potentially overlapping forms:

It is increasingly easy to create fake voices and avatars of people based on recordings of their voice and person. ElevenLabs announced that they requested consent from the estates of celebrities like Burt Reynolds to clone their voices and feature them in the product.

Just as there are laws that keep our images from being used to suggest we endorse something without our permission, similar laws and patterns will be needed for voice cloning.

Meta made the decision to sell their AI glasses without any indicator that they are actively recording. There have already been public cases where this has been used to harass others by recording them and putting up recorded exchanges online.

Returning to the limitless device, the approach the company initially took offered a novel pattern to record seamlessly while protecting the privacy of others. The technology is there to support an ethical approach to designing these experiences, but it is up to the company and the designer to use it.